When you read about anticipated changes due to IoT, Industrial IoT, or Industry 4.0, you inevitably come across the term business model. Usually, it is the conclusion based on the changes anticipated by the IoT: You have to innovate or change your business model. But more often than not, that’s all you get and you’re left to figure out how to do that on your own.

That is somewhat understandable, since it is not easy to change or create a business model, and it requires a lot of personal and organizational effort. This blog series was created to help guide you through that process in the context of IoT. Here, I will try to give you a more complete picture of the changes that IoT will have on business models and subsequently all businesses. To do this, I will lay out what I have learned thus far, show as many real-world cases as possible, try to point out critical aspects that are either often overlooked or harder to implement, and give you a perspective on this phenomenon based on my insights.

What are business models?

To get everyone on board, we’ll start with a short description of business models. While the literature contains quite a large number of frameworks and different definitions (Teece, Chesbrough, Baden-Fuller & Morgan, Magretta, Zott & Amit etc.), most of these have an academic approach and do not translate well into practice.

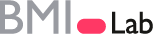

The St. Gallen Business Model Navigator, which is at the core of our approach, uses a business model description that is based on practical work and is more suitable for interactive workshops. This simplified approach is more expedient than complex canvas work, leading to more focused discussions. It is based on four dimensions or questions displayed in a triangle:

1st dimension: WHO (is our client?)

To describe the logic of your company, the client is at the center in each and every business model. Their needs and issues are at the basis of why and how your company works, otherwise there would be no one to pay you.

2nd dimension: WHAT (do we deliver to our clients?)

Here, the value proposition is described – what is actually offered to the client to meet their needs and how it solves their issues.

3rd dimension: HOW (is the offering created?)

To deliver the value proposition, companies need to execute certain processes and activities, using their resources and capabilities as well as coordinate with partners in the value chain.

4th dimension: WHY (is this financially viable?)

Finally, cost structure and revenue streams are described to explain how to make money with this business model.

Answering these questions gives a concrete, tangible picture of the (imagined) company or business unit – the basis for innovation. As soon as you change two dimensions or more, we talk about business model innovation (BMI). Changing just the WHAT dimension is a product innovation, while a HOW change would be a process innovation.

Why business models?

Before we dive deeper, I think it is important to know why business models, or thinking in business models, is actually helpful for companies in innovation and not just old wine in new skins. For this, we have to step back a bit, to understand the bigger picture.

What truly formed humanity into our current state is language. Language allows us to share experiences, stories, and knowledge with other humans, thus laying the foundation for society and the world as we know it. But language is not bound to the outer world, to perceptions we made or could make together, it can also express our inner life, ideas, and imaginations.

This allows us to express and thus create a common understanding of ideas and structures that don’t exist as solid objects in the natural world, such as laws, religions, democracy, science, money, and so on. These structures only work as long as a sufficient number of people believe or adhere to them. Yuval Harari calls these collective imaginations and he argues that these enable humans to cooperate flexibly with thousands or even millions of strangers. At the heart of these cooperation, networks lie fictional stories: Catholics go on a crusade together without knowing each other, soldiers of a specific nation risk their lives for each other because they believe in a common nation, lawyers can work together to save or sanction an individual because they believe in law, justice, and human rights – as well as in money they get paid for doing so.

Yet, as Harari says, “[…] none of these things exists outside the stories that people invent and tell one another. There are no gods, no nations, no money and no human rights, except in our collective imagination.”

Another powerful collective imagination are companies. In what sense do companies such as Ford, LG, and Google exist? They are not flesh and bone but can still own property and do not (necessarily) disappear when their founders die. Everyone in these companies and every asset could be dismissed or destroyed, but they would still exist in this world because we agree upon the existence of such companies.

Collective imaginations enable us to work together, where no other animal could, across geographic and communicative boundaries. They allow for efficient structures that do not exist in the objective reality, but that help us to communicate, act, and decide.

I would argue that the notion of business models can best be thought of as such a collective imagination. Business models are an abstract concept that describes how another abstract concept, companies, work on a higher level. Yet, this concept allows us to think differently about companies: we can see the whole logic of it more easily, we can discern the important parts, we are free to think about changing certain parts, and most importantly, this imagination allows us to share these findings and insights with each other, to act upon these in the solid world.

This is the way business models developed in the dot com era. Founders needed a way to describe their business to potential investors, in a fast, yet comprehensive, way. People who resonated with the concept could more easily imagine how it would work (or wouldn’t) and decide based on this short concept, instead of a 30-page business plan.

One of the most important aspects when working with people to generate new ideas or business models is to help them break free of conventional thinking – what we also call their dominant logic. This how we call the way they, their company, their industry, and the people they know have typically worked and the structures and processes they adhere to. This has worked quite well thus far, but blocks their creativity and inhibits their capability to innovate. There is a reason why we call it “thinking outside the box”.

If you’re caught within this box, seeing the company and industry from the inside and what works and why, but cannot see each part from above to get a better picture, you usually cannot come up with new and coherent ways to accomplish something.

Business models help us see the company or business unit “from above”, they show the most important parts, make it easy to identify issues, and, most importantly, make it easy to describe new ideas. This is why the St. Gallen Business Model Navigator with their business model pattern cards is so effective. These patterns of business models build a basis for ideation on a higher abstraction level that is easy to grasp. If we truly stand on the shoulders of giants, we should make use of that.

For more information and inquires on business model development, the BMI methodology, the BMI tools, or have feedback, please contact Richard Stechow.