BMI Think Tank travelled to China for a Business Model Innovation Study Trip. A great opportunity to understand how China has evolved into a global innovation power.

(This is the first in a series of two articles about innovation in China, where we share the insights gained from the research trip we made to China with some of BMI Lab’s clients in August 2017).

China is no longer just the home of copycats. Massive investments, a huge market and the hiring of worldwide talent has boosted the Chinese innovative ecosystem. In fact, today, some of the biggest companies in the world are based there. But how was this possible? How did China succeed in innovating so much within the last decade? At BMI Lab we wanted to learn how they did it, so we travelled to China with some clients, visiting companies, factories, labs and universities to find the recipe for the secret sauce of Chinese innovation.

China’s road to innovation

The corporate might of current day China is undeniable. For instance, in Q3 2017, Tencent, the Chinese Internet company that developed WeChat and QQ, overran Facebook in terms of market value. At this moment in time, Tencent is the 5th most valuable company in the world, while Facebook is the 7th. And the Chinese marketplace Alibaba is now the 6th, close behind Amazon on 4th place.

Moreover, during the past decade, China has become a leading global power in several areas of the digital economy. For instance, China´s share in global e-commerce is now more than 40 percent, larger than the combined value of those of France, Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States.

This graphic shows the differences between the market value of US, Asian, and European Internet and Tech companies. Right now, Chinese companies are directly competing with their American counterparts (Source: Wikipedia).

Nevertheless, those achievements could not have been possible without proper innovation policies and practices being responsible for the creation and growth of an economy capable of creating and sustaining big, innovative, companies. Three actors have been leading the Chinese innovation ecosystem for the last decades: government, the so-called frugal innovators and the last wave of innovators comprised of serial entrepreneurs, business angels, venture capitalists and big internet companies.

The role of Chinese government in innovation

The government has always been a powerful economic force in modern China. We have to bear in mind that the Chinese government has a long tradition of direct intervention in the economy. China has gone through 13 five-year plans up to this point and the country's entire economy is KPI driven. Right now, the government is running a five-year plan focused on scientific advance and green development.

To that end, China operates in many fields as a huge corporation that develops innovation hypotheses to prioritise and allocate budgets. Right now, as part of the current five years plan (ending in 2020), China is focusing on:

Aviation and aerospace.

Agriculture.

Electrical power.

New-energy automotive.

High-end robotics.

Next-generation information technology.

New materials and composites.

Rail transportation.

Maritime engineering.

Biomedical and advanced medical equipment.

The growing percentage of funds allocated to technology innovation clearly shows China's ambition on innovation leadership (Source: Prof. Dr. HAN, Zheng , Chair of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, Tongji University Shanghai)

The Chinese administration, through its various regional branches, is focusing on the promotion of strategic emerging industries in these areas, according them preferential treatment with subsidies, tax breaks, bank lending and direct financing. The goal is very clear: the share of the global GDP for all those industries should increase to 15% in 2020. This kind of planning is uncommon for Western economies and is one of the main reasons for China's innovative success.

Finally, the administration is playing an active role in building world-class infrastructure to support digitisation as an investor, developer and consumer. It also gave the Internet giants of China, Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent (also known as BAT) a free hand to experiment before setting up regulation, especially in the privacy, data management and property rights fields.

So, we cannot understand Chinese innovation without its intense, direct state intervention. The country’s economy is still very much driven by public policies, although a significant reduction of the role of the state in the economy is a stated goal of those responsible for planning the next stages of Chinese economic growth.

Prof. Wolfgang Drechsler, from the University of Tallin, lectured the BMI Think Tank group about how bureaucracy can promote innovation. China is the best example for that!

The first wave of innovators in China: Frugal innovation.

The second driving force for innovation in China during the last few years has been so-called frugal innovation, which started around 20 years ago. This concept refers to the first wave of Chinese innovators, who developed cheap and reliable solutions for the majority of the Chinese people, a huge, but low-income, population. A great example of that is BYD.

BYD was founded in 1995 by a chemical engineer, Mr. Wang Chuanfu. The company started as a manufacturer of cheap batteries for mobile phones, with a “Western-style” and decent quality, but adapted to Chinese purchasing power. BYD became the second largest battery company in 2002.

In 2003 BYD created an automotive subsidiary, specializing in building electric cars. Its approach to car manufacturing also represents quite accurately the innovation philosophy of these early Chinese entrepreneurs: rather than expending years on design, BYD takes Japanese cars as a benchmark and adapts them to Chinese tastes through a process of reverse engineering.

As a result of this practice, BYD's cars' time-to-market is significantly faster and the price much lower, allowing most Chinese middle-class households to buy one. Furthermore, BYD prefers to test every design in the market, rather than attempt to perfect a model before its launch.

As a result, later versions are usually better and the company can tolerate a negative impact on the brand caused by earlier versions. The best part of this strategy is that risk is reduced, since the company relies on successful designs to adapt their own. As BYD’s CEO Wang Chuanfu says: “I will not build a car starting from zero! We must build the car based on the most advanced automobile platform in the world!”

The main features of the development process of new cars in BYD explained in a graphic (based on the info provided by Prof. Dr. HAN, Zheng , Chair of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, Tongji University Shanghai).

This brand became a symbol of economic success and this approach shows how the first innovators broke through in China: by adapting western technologies to the cultural and economic circumstances of China bringing new products with reasonable quality and low prices to the growing middle-class.

The second wave of innovators in China: BAT, or the rise of world-class giants.

During the last ten years, a new wave of highly innovative Chinese companies has emerged from scratch, with some of them even reaching the top levels of the global economy. We are talking about corporations like the three most aggressive and biggest internet companies in China which have global reach - Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent, or BAT as they are collectively known - and Huawei, Xiaomi or ZTE, which are creating a multi-industry digital ecosystem that touches every aspect of consumers' lives.

Some figures can help us understand the magnitude of these companies:

Overall, China's venture capital sector has been growing rapidly. From just $12 billion in 2011–13, or 6 percent of the global total, to $77 billion in 2014–16, or 19 percent of the worldwide total.

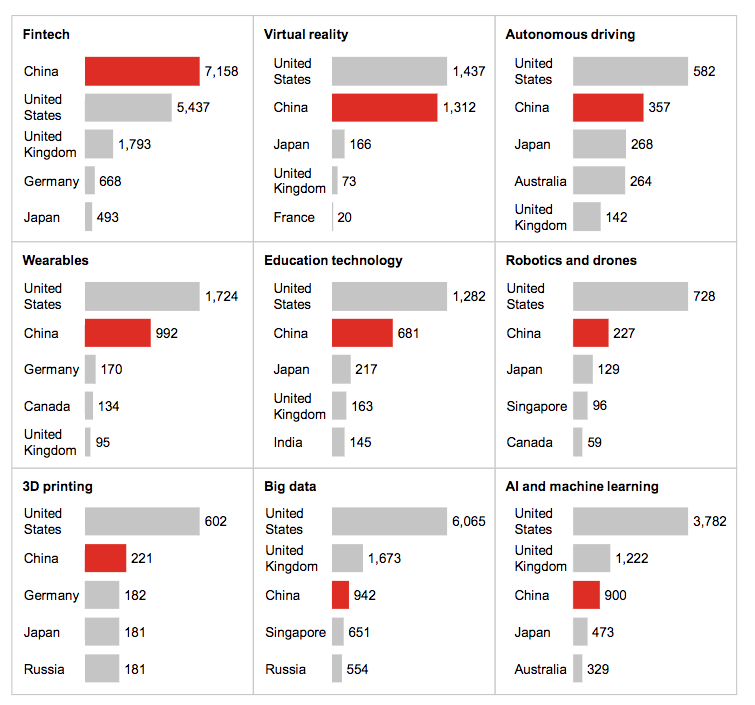

The majority of venture capital investment is in digital technologies such as big data, artificial intelligence (AI) and financial technology companies.

China is in the top three in the world for venture capital investment in key areas of digital technology including virtual reality, autonomous vehicles, 3D printing, robotics, drones and AI.

In China, BAT and other tech companies invest heavily in start-ups, building, through VC, a rich digital ecosystem that is now growing exponentially. Their strategy to build a dominant position in the digital world is clear: they remove inefficient, fragmented and low-quality offline markets while driving technical performance to set new world-class standards. Once achieved, they have built excellent capabilities to tackle new challenges and move abroad entering another market.

Venture capital investments in leading technologies, 2016 (Source, PitchBook; McKinsey Global Institute Analysis). China is in most cases in the first or second position.

Throughout this new ecosystem, new unicorns and start-ups are proliferating, propelled by funding from their big patrons. One in five start-ups in China is funded by BAT or BAT alumni, with 30% of them received funding from these three big players. Xiaomi, which is moving outwith the mobile phone market to embrace other areas of customer life-style, is investing in companies developing new houseware technology and allowing them to use Xiaomi's brand.

The rapid growth in the digital sector is also boosted by the close relationship with hardware manufacturers. The availability of cheap and reliable phone and related device manufacturers facilitated the quick adoption of digital solutions for the majority of Chinese people, creating a virtuous loop for innovation adoption among the majority of the population.

The best example of this kind of ecosystem is the so-called Digital Delta, based in Shenzhen. This city on the Yangtze river delta was once widely known for its copycat products but is now the centre for China's open innovation. It has become the hub for the majority of hardware-based start-ups. There, you can find the Huaqiangbei district, one of the largest electronics markets in the world and home to big incubators like HAX.

In this same city, you can also find companies like DJI, the biggest drone manufacturer, with a 70% share of the customer drones market. DJI has an open platform for developers building new hardware and software for drones in several fields such as farming, forestry, public buildings, etc.

But it is not only hardware: Chinese companies are also specialising in handling huge amounts of data, extracting valuable information and performing top-level innovation from it. For instance, Xiaomi, which sees itself as a software company, has a project to use data from vacuum cleaners and learn about their clients' apartments, domestic life and behavior to develop new solutions based on that.

To summarise, Shenzhen is a perfect example of the kind of innovation policies that China is taking: a place where the government strongly supports innovation promoting some big players who are leading the way, investing heavily in creating new tech-based ecosystems, and where start-ups can find some interesting niche markets.

A huge market with some problems ahead

As we have seen, several factors lie behind the huge growth of innovation and innovative companies in China. The government, frugal innovation companies, and internet giants stand out as the main actors, but none of them can explain by themselves the rise of the Chinese innovation economy. We have also to bear in mind that the Chinese market and society has been the fundamental foundation for all these achievements.

The sheer scale of Chinese middle-class digital users.

China is an enormous market where early adoption of cheap technologies brought a critical mass of digital-native citizens willing to adopt early any new technology coming to the market. As McKinsey reports, “In 2016, China had 731 million internet users. That’s more than the European Union and the United States combined. China also has 695 million mobile users, compared with 343 million in the EU and 262 million in the United States. Digital native internet users number about 280 million, nearly the same as the total number of US internet users. China’s large user-base of mobile and young people enables faster adoption of digital.”

Furthermore, these digital natives are savvy and passionate about new technologies. One example can help us to understand the level of tech proficiency of Chinese digital users:

In mobile payments, penetration among China’s internet users has proliferated from just 25 percent in 2013 to 68 percent in 2016.

The value of China’s mobile payments was $790 billion in 2016, 11 times that of the United States.

Graphic showing the growth of mobile payments users in China between 2009 and 2013, compared to not mobile payment users. (Source: Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, Celent).

Some problems ahead

Despite this great advantage, there are some problems ahead coming from the ageing pyramid of the Chinese population, and the particular traits of the Chinese economy:

Despite its demographic might, the younger Chinese population (between 16-50 years old) is dwindling in percentage terms. The young population will reach its peak in 2018 and will start to decline from that date on. This is a real threat for consumption, but also for human capital which begins to show real symptoms of scarcity: right now, talent is not plentiful in China - a real problem for the innovation ecosystem.

Ultimately, China is already moving from a policy-driven economy, with a big share of investment in GDP and its specialisation as the “workbench of the world,” to a market-driven economy. One where consumption counts for the larger share of GPD with a focus on an innovative, service-driven economy. As premier Li Keqiang says, “China needs to develop the 'twin engines' of popular entrepreneurship & mass innovation.”

This graphic shows a projection of the demographic development in China: there is clear decline expected for the upcoming decades, especially on the segment between 16 and 50 years old (Source: HSBC).

Nevertheless, China, right now, is an innovative giant, capable of creating new businesses, spearheading the R&D in many fields and capable of exporting new business models globally. The country has undergone a huge leap forward and the coming years will be crucial to overcoming its current problems and becoming the world's leading economy in innovation. Interesting times ahead!